Written by Keloni Parks, Reference Librarian, Main Library

In the early-to-mid 1900s, the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County had two branches for Black community members, the Douglass Branch Library in Walnut Hills and the Stowe Branch Library in the West End. Relics from this history, including photographs, are on view at the West End Branch Library during May as part of the Black Branches: Stowe, Finley, and the West End exhibit. Here’s a peek of the display.

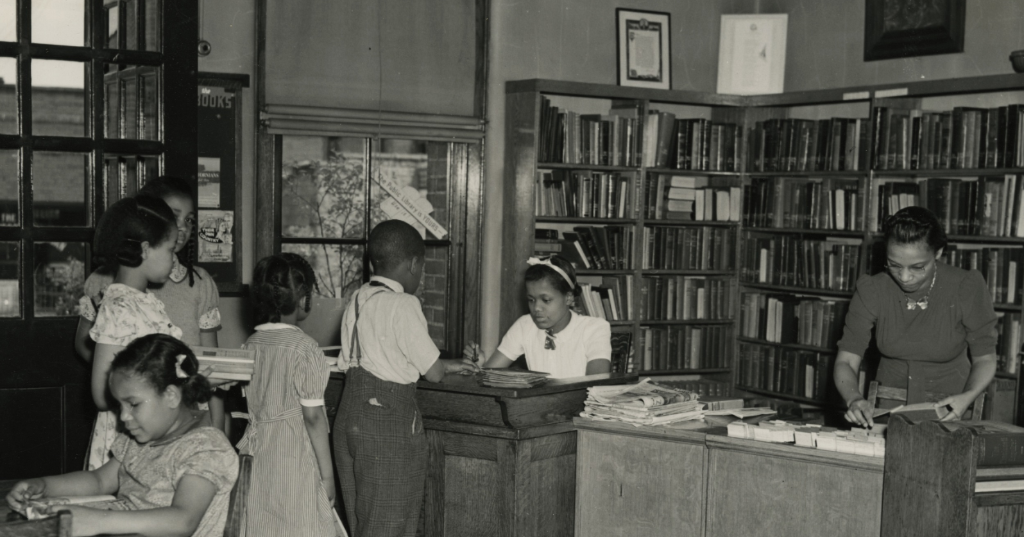

Douglass Branch Library

Located in Frederick Douglass Elementary School, the Douglass Branch Library opened in 1912 and was the first library for Black residents north of the Ohio River. Although the newly opened Walnut Hills Branch Library was only five blocks away, and the Public Library of Cincinnati didn’t prohibit Black customers, it was believed that they would be better served at the Douglass location.

During its 42 years of service to the community, it had five branch librarians, Mary G. Finley, being its most well-known. She was the branch’s fourth librarian, and managed the branch the longest, from 1927 to 1948. After managing the Douglass location for 21 years, she became the branch librarian at the Stowe Branch Library location.

Stowe Branch Library

Eleven years after opening Douglass, the Stowe Branch Library opened in the Harriet Beecher Stowe Public School for Negroes, becoming the second location of the Public Library of Cincinnati for Black cardholders. Like Walnut Hills, the West End already had a library, the Dayton Street Branch, but its large Black community near West Seventh and Gest streets justified its creation.

When the branch opened, it struggled to register borrowers since many of the residents were new to Cincinnati, and often illiterate. The school was a beacon of light for the community, which was considered congested and problematic by social services and law enforcement.

Stowe’s first librarian was Hattie Mae Walker, who worked at the branch for 25 years. Walker believed library collections should be adjusted for the communities they serve. She felt that it was important for Black people to know about the “accomplishments of their own race.” Hence, many of the books at the Stowe Branch were by and about Black people.

Add a comment to: Black branches of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County